Since the late nineteenth century, Italian emigration has been extensively studied, but the various surveys and numerous essays on the phenomenon reserve the most attention to male emigration and -- of course -- read female emigration according to the ideological parameters of the time.

The first to suffer the consequences of male emigration were the women who remained at home: they cared for children and the elderly, were housewives and worked in the fields, spinning and weaving, and finally, in place of the absent men, took responsibility for economic interests. Thus there was a true feminization of so many towns in the Italian regions most affected by migration as very often it was entire family groups of males who emigrated, all together or staggered over a short period of time.

The takeover of women in men's tasks is well evidenced in notarial deeds, which, in a steady increase since the late 19th century, show women's names as contractors in agreements of all kinds, and particularly in purchase and sale contracts.

Then, gradually, women gained space in the world of work. The first industrial sector in which female emigrants had a place was textiles, beginning in the French factories of Lyon. Instead from engagement as housewives arose and multiplied, especially in North America, boarding, that is, keeping compatriots boarded. It was a job considered typically female, along with that of various home packing, because it allowed women to remain "angels of the hearth" while earning and contributing to the better running of the family ménage.

In Brazil, for the fazendas, mostly coffee producers, women maintained the traditional role of wife, mother and "dependent" worker. In fact, the owners tended to import entire and numerous households, whose members, while all employed in field work, were managed exclusively in that relationship through the traditional mediation of the breadwinner.

Nannies

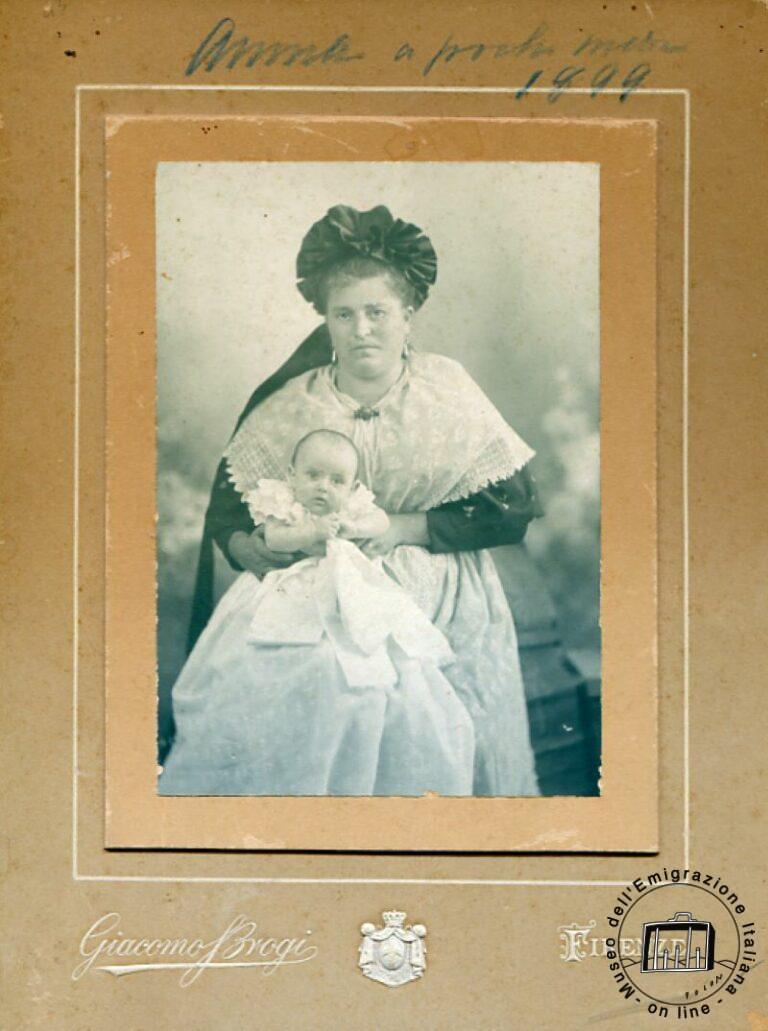

Women also went alone in emigration becoming wet nurses and maids. The baliatico was typical of Tuscany, Latium, Piedmont,Veneto and Friuli, regions characterized by seasonal male emigration, and along with that of the men, traditionally the first to leave, a migratory current of only women was established who devoted themselves to the baliatico. In rural Italy, women had as their "wealth" milk to sell: they thus nursed the children of local lords and notables, or engaged in charitable institutions, especially in kindergartens for abandoned children, the "exposed," and finally went abroad with the prospect of good pay.

A wet nurse, in general, earned much more than a laborer and enjoyed considerable benefits: a well-stocked wardrobe with pretensions to elegance; numerous personal and household linens; ornaments, referred to precisely as "wet nurse jewelry," which included necklaces, brooches and earrings, often of red coral; and the certainty that for many months one would not go hungry, would live in beautiful and comfortable homes, cared for and respected by the host family. It was undoubtedly a lot even if the price one had to pay was entrusting one's child into "mercenary hands," as the well-wishers hypocritically put it, hands that in many cases were those of other women in the family.