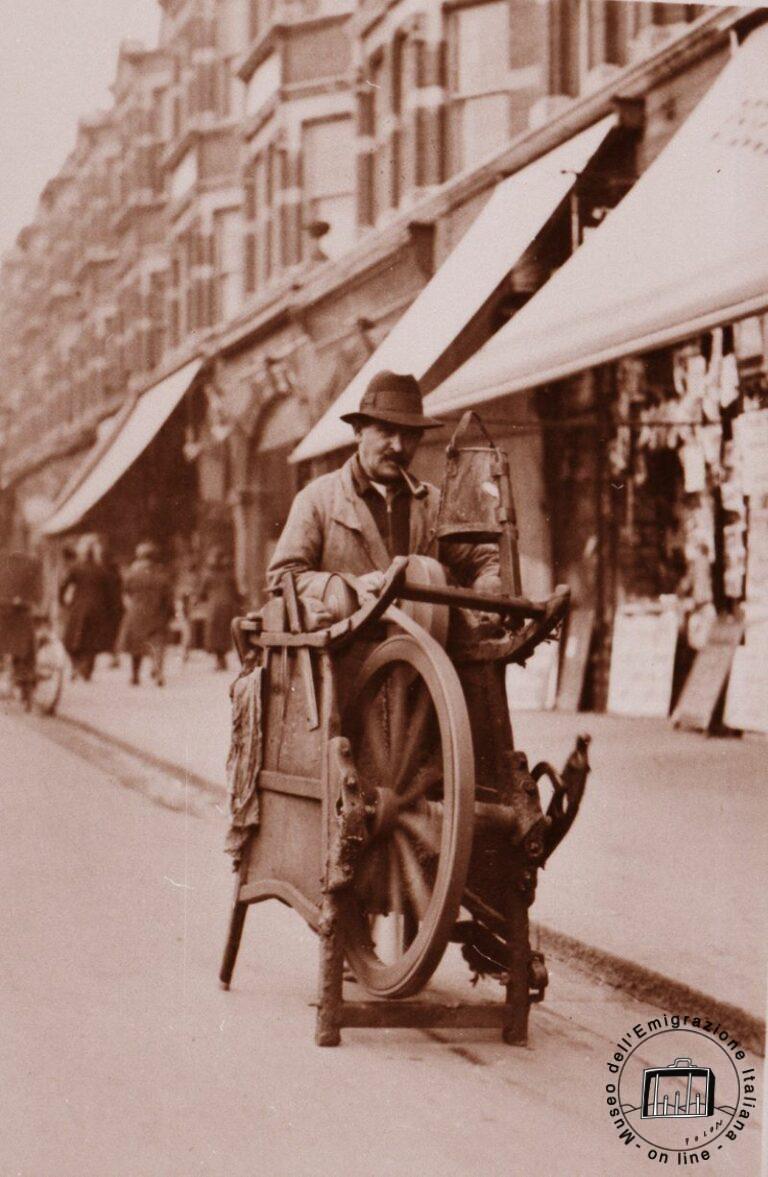

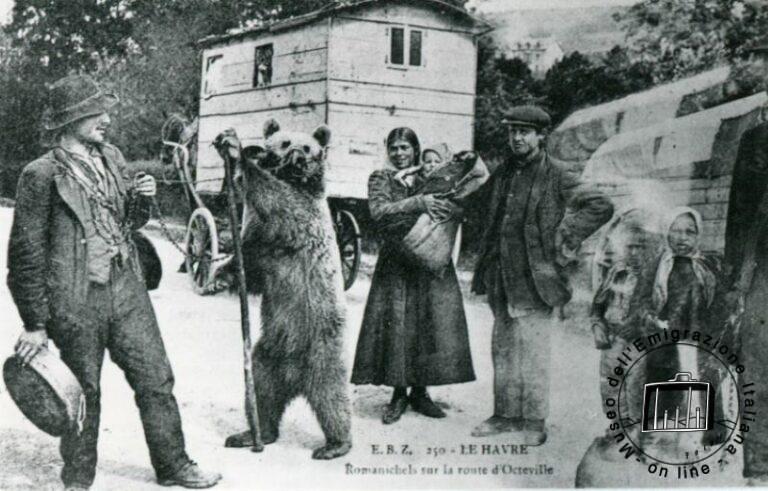

Vanguards of actual emigration were those who practiced itinerant trades and were therefore able to report news and information useful for lasting migratory projects. In Tuscany, peasants went to Corsica, for farm work, and then to France, attracted by better wages, although the most common skilled trade was that of figurine maker. Ligurians crossed the Mediterranean and went to North African countries for seasonal work. Wandering musicians from all over Italy departed for most European countries, and then for the Americas, while print and small-merchandise sellers, as well as lumberjacks and earthworkers, left the eastern regions of the peninsula. Savoyard chimney sweeps were present especially in France.

In fact, "wandering professions"-whether musicians, acrobats or animal trainers, sellers of various goods-constituted as many variants of peasant begging that had been resorted to for centuries in times of great misery.

As transportation improved and the great emigration began, the routes of the wanderers expanded, reaching first all European countries and then the Americas. Police authorities frowned upon them, constantly accompanied by children, whose employment was often only a means of disguising the begging they were forced to do. Their miserable lot aroused the pity and indignation of the ruling classes, which, divided for and against emigration, exploited the argument in favor of their own thesis. In reality, the phenomenon took place on its own, vainly pursued by laws tending to regulate child labor. Sometimes it was the fathers themselves who took their children with them or handed them over to reliable people in the hope that, along the ways of the world, they would learn to practice an activity that could feed them.

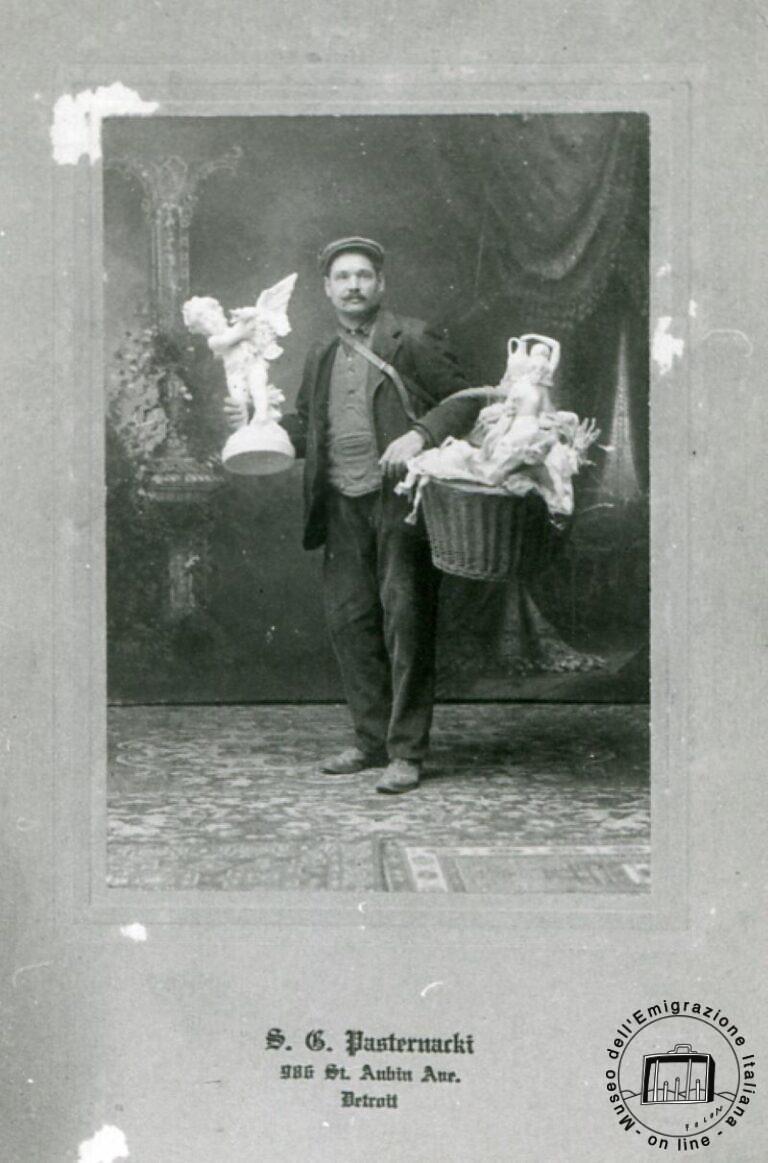

"That begging disguised with the symbols of art" was the most widespread and visible image of the new kingdom of Italy on the streets all over the world. It is certainly not possible to deny the cruelty of "masters" toward minors brought and employed in foreign countries. Many times an apprenticeship relationship, which characterized so many trades carried out both in Italy and abroad, degenerated into speculation, into shady trafficking, but this occurred to a lesser extent for the sellers of figurines.

On the other hand, families in poor economic condition could consider with relief the fostering of a child to a master: one less mouth to feed, a small sum received as compensation, and the hope that the little one could learn the trade of a salesman and, later, of a real figurine maker and even a master. "Campaigning" abroad meant leaving for a period of twenty-four to thirty or thirty-six months. The master, the owner of the forms, formed his own company, which included various professional skills: the moulder, who made the figurines with the forms; the deburrer, who made them uniform; and the colorist, who painted them.

Once the chosen destination was reached, the workshop was set up and the figurines produced were sold on the streets by the boys. They represented madonnas and saints, the Pope (appreciated not only by the Italians but also by the Irish, Catholics), various heroes - Garibaldi sold well everywhere - and figures from the country in which they worked (in the United States, President Abraham Lincoln was in great demand).

A special craft: the figurine maker

The first of the specialized trades to spread, starting especially from the Lucchesia, to all the ways of the world was that of the figurine maker. Already between 1870 and 1874, years in which an industrial survey was carried out, the art of the figurine maker appeared among the jobs and trades practiced by Italians abroad.

In Paris, for example, there were more than a dozen of them, and at least six practiced their art to "a higher degree, becoming model makers," while there were about two hundred "figurist" workers and the number of the garons who sold figurines on the streets was unknown.