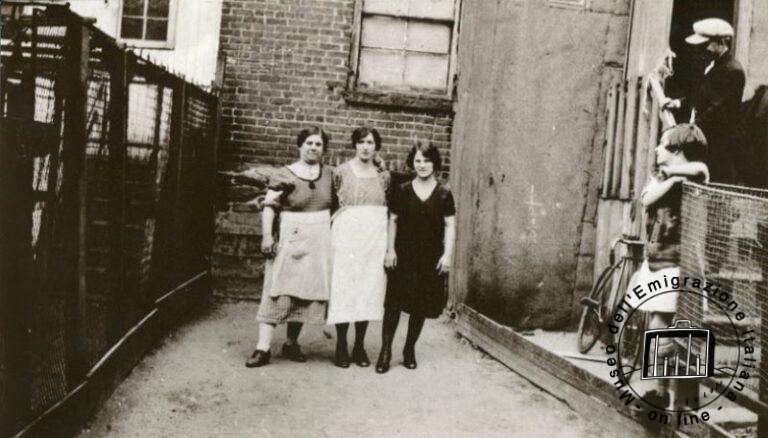

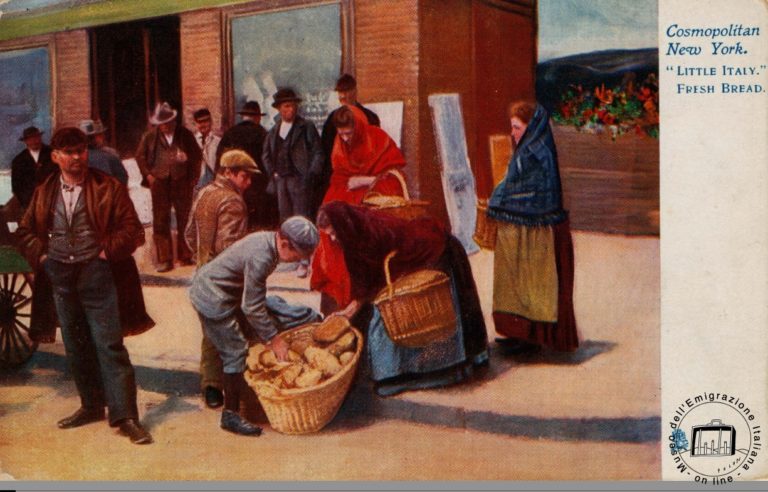

The streets of Little Italy, as the Italian neighborhood was called in the United States, were narrow, crowded, dirty, overlooked by dilapidated tenements. The tenement was a large tenement: often, it had shared bathrooms (on the landings or in the courtyard) and entry into almost uninhabitable, dark alleys.

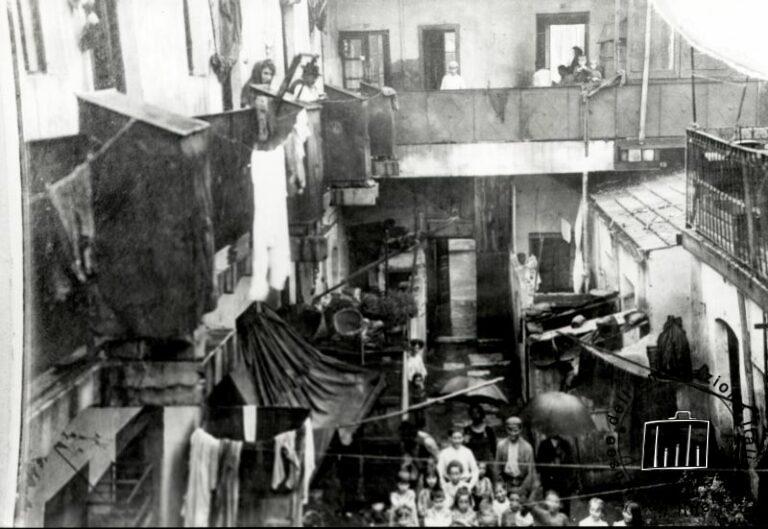

The immigrant who had just arrived in the new reality found refuge in "Little Italy" and, oppressed by nostalgia and deep inner loneliness, found relief and escape in integrating into a group that substantially reproduced the values and behavioral codes of the one of origin. Instead, in Buenos Aires, emigrants, not only Italians, found lodging, in the area near the port, in once stately buildings converted into immigrant housing, the conventillos.

The classic conventillo scheme involved a parallelepiped shape, first floor and second floor, with an inner courtyard where, in common, essential services were located. Lively photos of conventillos in Buenos Aires and of Mulberry street in New York help us understand how those places became community centers for the re-production and distribution of culture.

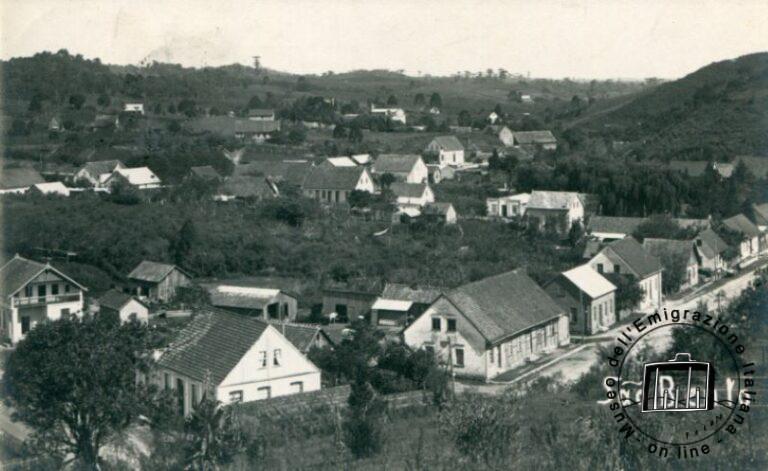

This was the origin of Italian neighborhoods in large American cities, with varied names, but in which the streets had the function of the village square, of places where a common cultural heritage was restructured and condensed, suspended between ancient roots and new "frontiers."

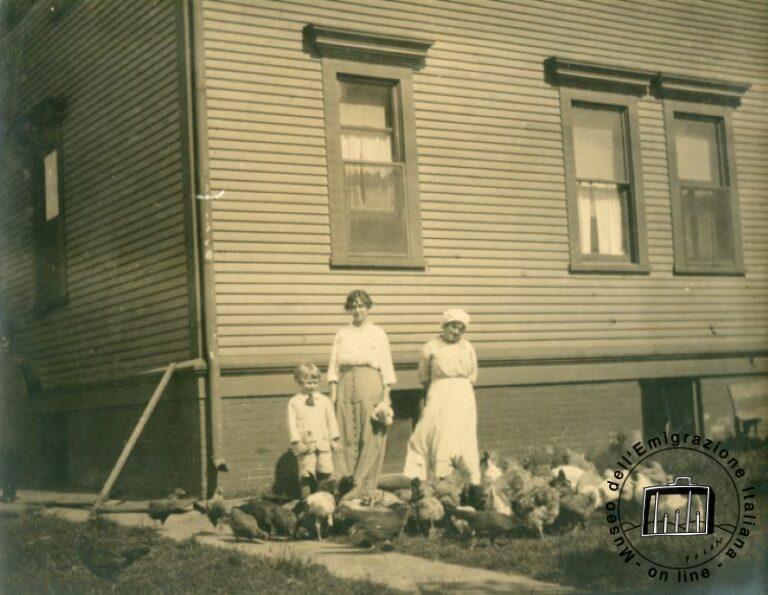

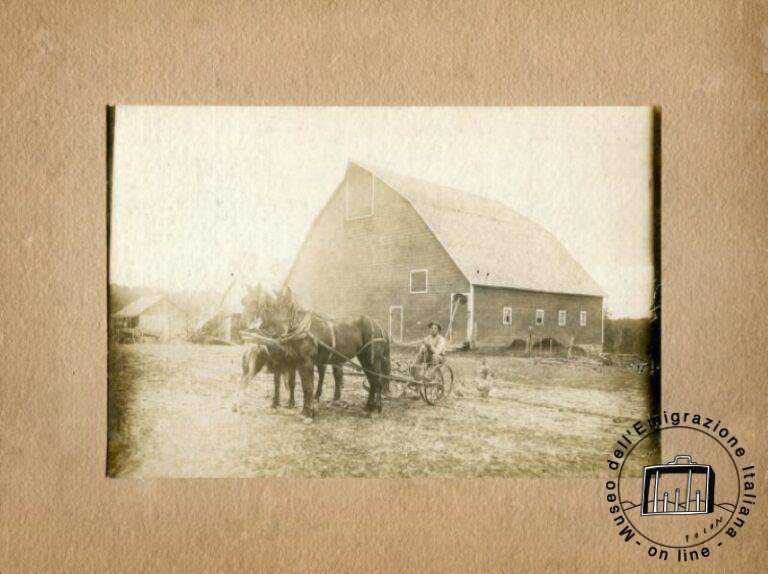

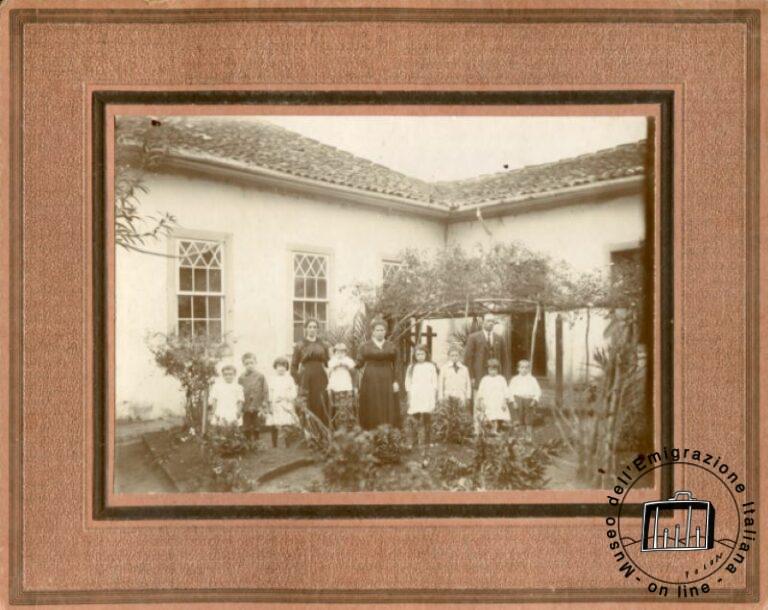

Later, the achievement of a proper home became one of the most reassuring "signs" of the path taken and the "progress" made: home is the place where everyone can simply be themselves.

Home is nest and fortress; refuge for those with "inside Italy, outside America," still largely to be conquered. And the photos are almost biographies written by the emigrants themselves.

From the Cresci Archives two different accounts: Augustin Storace is a merchant and bombero (firefighter) in Lima. Provided with a good education, he uses the lens to fix scenes of family life. Benny Moscardini, transplanted to Boston, makes less private use of photography: he portrays young men and girls in the neighborhood, the streets decked out in honor of General Diaz, and, on a trip to Italy, even a dock in New York Harbor. Storace's world is all collected between home and workshop; Moscardini's is projected outward.