The title of this chapter is, in a way, provocative because, among the images published, the great absentees are precisely the letters. Letters, the words that travel the world, are the thin but strong thread that holds together the two sides of a family divided by emigration. They express, not always explicitly, the suffering that comes from being uprooted from one's world, the isolation into which one is plunged and the discrimination to which one is subjected. At the same time, they make the eyes of those who have remained in the country flash to the great possibilities offered by the land of arrival and thus entice others to leave.

A general characteristic of emigrants' letters is the transposition of oral expression into writing: they write as they speak with the addition of questionable spelling (especially of foreign words and Italian words foreign to their own linguistic heritage) and improbable punctuation.

But the "real" letters are the photographs that the emigrant sends and exchanges with family, relatives, friends. So the question is: can emigration be photographed? In theory, in order to give an exhaustive account of this phenomenon, one would have to have a great many pictures; in reality, however, each photograph tells many things and contains varied insights and reasoning.

At Ellis Island that well-ordered group of people in the large gathering hall and squeezed, by photographic illusion, by "bars" that make them look like prisoners impresses as much as, perhaps more than, the statistical data.

And in the photos, numerous in number, taken of emigrants against the backdrop of care facilities -- whether Catholic or secular; from the period of the great emigration or the post-World War II exodus -- the pattern is always the same: the men are taken from behind, burdened by the weight of luggage, and suggesting the help, almost the embrace offered to them.

When the photographic medium was within everyone's reach, every emigrant was able to "create" his or her own album of images, constructing and taking care of all the details of his or her "beautiful pictures." If one looks, for example, at the people portrayed near cars, one may notice that their hands are well placed: do they not unconsciously signal the effort made to obtain those symbols of social and economic progress?

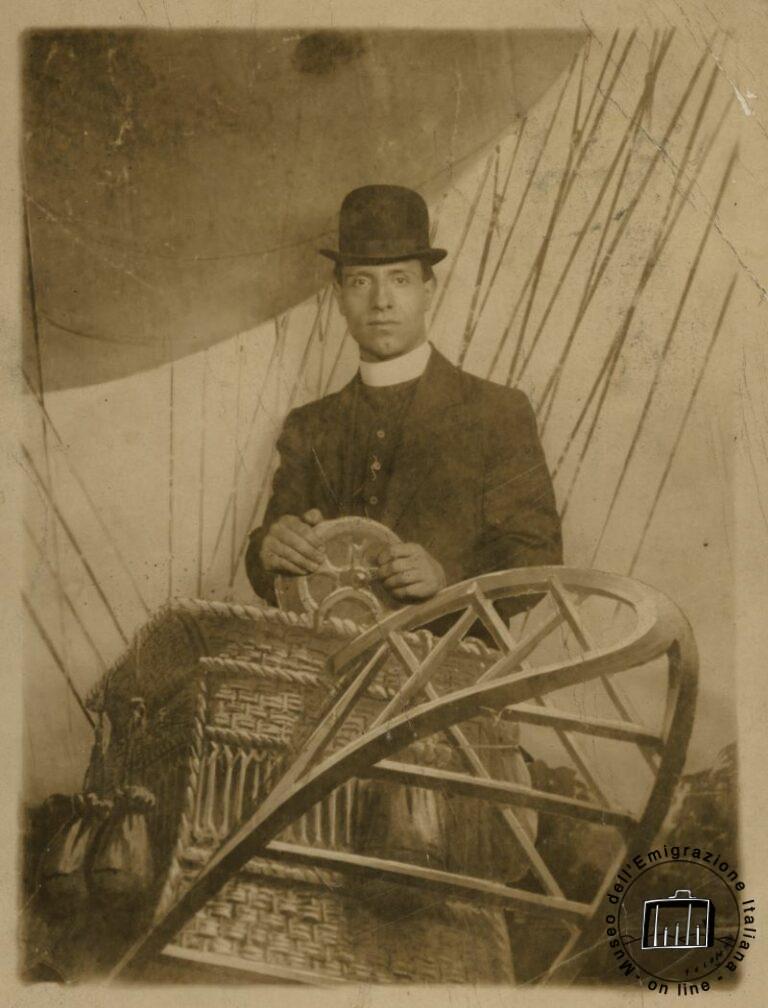

Also part of this heritage of memories are less formal images that tend to surprise. In these cases, a bit of exoticism doesn't hurt, and people pose in traditional clothes of the host country or assume lighthearted poses: from posing as men of the world sitting at a bar table, laden with glasses and bottles, to disguising themselves, with extreme seriousness, as cowboys and gauchos or pretending to be flying in a hot air balloon.